Clean-water evangelist

Minnesota's bragging rights as "the land of sky-blue waters" have a staunch defender in Jenn (Cline '08) Radtke.

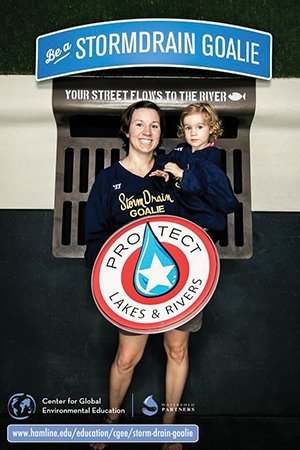

Jenn Radtke was joined in August by her 2-year-old daughter, Linnea, in promoting practices that keep fertilizers and toxins from feeding into the Twin Cities’ rivers and lakes.

Minnesota’s bragging rights as “the land of sky-blue waters” have a staunch defender in Jenn (Cline ’08) Radtke. A water resource educator for the Washington Conservation District in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, Radtke gets the word out to residents, businesses and elected officials on addressing issues like water pollution and wastefulness.

“I love working in this field,” says Radtke, who graduated in environmental science and is now on a mission to take care of the Earth’s most precious resource. The Twin Cities area gets more than 70 percent of its drinking water, as well as water for lawns, parks and other landscaping, from groundwater supplies. Water levels in local aquifers have dramatically declined in recent years, as residents noticed the too-dry ground and record-low levels in nearby White Bear Lake.

One remedy that Radtke and her colleagues encourage is replacing lawns of thirsty grass with native plants, a practice that also reduces water pollution. Grassy lawns tend to be treated with copious quantities of fertilizers and pesticides — poisons that, when it rains, get swept away in stormwater. Stormwater also carries pollution from driveways, parking lots and other dirty sites – all of it running down storm drains that directly feed into the Twin Cities’ lakes, streams and rivers.

Native gardens aren’t only more practical, says Radtke, but they’re more beautiful and vital than grassy patches.

“Lawns are ecological dead zones,” she says, “while native plants are home to bees, butterflies and birds.”

Rain gardens, specially designed to act as holding tanks for rainwater, are a solution favored by Radtke to the problem of polluted runoff. Rain barrels can be enlisted to collect water for later use in the garden.

Radtke presents numerous workshops in the community on the benefits and how-to’s of rain gardens. She’s particularly pleased with the blossoming of rain gardens at local churches, something she has played a key role in through her agency’s Green Congregations program. In a recent issue of the newsletter she writes for the program, she reminded dog owners to clean up after their pets to avoid “sending fecal coliform bacteria and E. Coli into the Mississippi and St. Croix Rivers whenever it rains.”

The church Radtke attends has a rain garden, as well as a mission that provides sanitary drinking water systems for communities in Africa and Iraq.

“In many countries, having ‘running’ water means running a mile or more to get it and bring it back – and oftentimes it’s not even clean,” Radtke said. “How incredibly lucky I am to wake up in the morning, turn on my faucet and have clean water.”