Expecting anything, expecting more (when you're expecting)

Researchers at Cal Lutheran and Stanford University are working to improve health outcomes for mothers.

To anyone who would listen to her after her baby was born, one woman complained that she could not breathe and felt as though her heart would burst. “You’re having a panic attack,” hospital staffers repeatedly told her. At home after being discharged, she felt the same way. She needed air. Was anyone going to help?

“It takes her general practitioner, who has known her for years, saying, ‘You really don’t look well,’ doing an EKG, and saying, ‘Your heart isn’t acting normal,’ and referring her to a cardiologist, who diagnoses her with a pregnancy-triggered heart condition, a potentially deadly heart condition which, again, the OBs and the nurses in the hospital had completely brushed off as a new mom having panic attacks,” said Adina Nack, a Cal Lutheran professor of sociology who is collaborating on a research study about traumatic experiences in childbirth.

In all, researchers at Cal Lutheran and Stanford University have interviewed more than 60 mothers, spouses, family members, delivery doctors and nurses, doulas, physical therapists and other medical and psychological specialists. They aim to understand complications in pregnancy and childbirth from all of these vantage points, and ultimately to improve health outcomes for mothers through better education, screening and treatment.

The three principal investigators on the study are up to that challenging task. Jamie Banker, a Cal Lutheran marriage and family therapist who has trained medical residents, has expertise in postpartum depression and family mental health. Stanford School of Medicine sociologist Christine Morton researches maternal safety and develops quality improvement toolkits for maternity doctors, nurses and midwives in her role at Stanford’s California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. And Nack has spent her career trying to understand the stigma attached to many sexual and reproductive health issues.

As Morton observed early on in the project, scholars have pretty good data on deaths of mothers and infants in childbirth. But there are no similarly reliable numbers on “maternal morbidities,” the complications and injuries that women suffer during labor and delivery, which may be life-threatening and which often have lasting effects. Severe hemorrhage, preeclampsia, pelvic floor damage and fistulas are some examples, among more than a dozen adverse obstetric events that, as a rule, no one’s expecting.

The best estimates suggest that for every death in childbirth, about 50 women in the United States have close brushes with death and 100 suffer severe adverse events. That translates to 70,000 severe cases each year in this country.

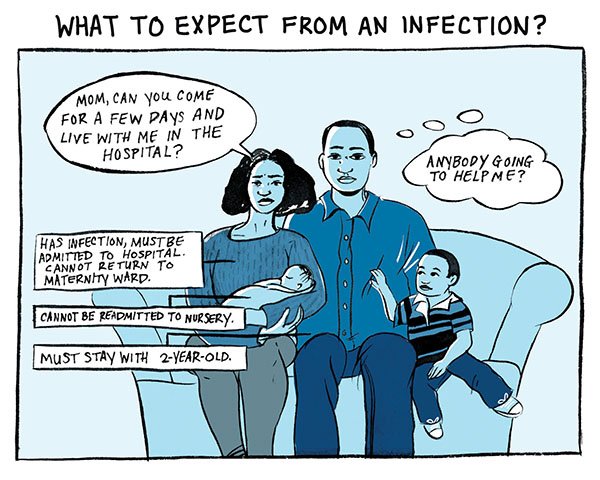

Precise figures are hard to come by partly because maternal morbidities often go undiagnosed until long after the women are discharged from the hospital. These injuries and illnesses are rarely connected to childbirth medical records, the primary sources for maternal health data. And for reasons the research team has not resolved, delivery doctors hardly ever refer mothers to specialists for treatment of childbearing injuries or psychological symptoms likely caused by physical birth traumas. (“If you know a patient has almost died,” asks Nack, “how could you not think that their mental health would also need to be cared for?”)

Regardless of educational level, women report that they did not see the complications coming. They didn’t know they could end up with long-term bladder control problems, chronic sexual dysfunction, increased risk for heart disease, or infertility. No one had told them. In many cases, no one advised them to seek treatment where appropriate. Problems ranging from urinary incontinence to organ prolapse can manifest years and decades later, long after the time for effective treatments has passed.

In a disturbing pattern revealed by the study, medical professionals respond dismissively to mothers’ complaints. “That sounds like a normal amount of bleeding to me,” one woman is told over the phone. Another seeks medical care for postpartum incontinence and hears for the first time in her life that a woman cannot expect to look and feel the same again after a vaginal delivery.

“There’s this narrative of, ‘You survived. Whatever happened to you while you were giving birth, you survived, and you have a healthy baby, and so now you’re supposed to be a happy mom and take care of your baby,’” said Hannah Conner, a Cal Lutheran senior and research fellow on the project, originally funded by the university’s Center for Equality and Justice Fellowships for Research in Service of Communities.

It’s not lost on Conner, age 21, that she’s the only member of the research team who doesn’t have a child. A double major in criminal justice and sociology, she was new to the subject of maternal morbidities when she began reading dozens of interview transcripts and working on a review of the available scholarly literature. Now she sees the issue everywhere.

“Before this project, you could hear little details. But there’s more behind closed doors,” she said. “People who’ve already had kids might talk about it with each other…. Knowing that I haven’t gone through any of it, they might not be comfortable talking to me about it. Which I understand.”

In every peaceful-looking city and town, Conner realized, a minority of new mothers is fighting desperate struggles. One woman has a seizure while driving herself and her baby to the hospital. Another suffers postpartum flashbacks and refuses to visit a hospital. Their testimony, on paper, makes them sound like people back from war.

These issues are not seriously discussed in public, with the exception of at least one online forum dedicated to birth injuries. Publicly, in fact, the subject of maternal morbidities comes up in two unserious ways: as a joke or a sales pitch. Nack’s ears perked up, for example, at a comic soliloquy about sexual dysfunction in the 2012 filmThis is 40. It begins, humorlessly, “I don’t have any feeling down there anymore. I have nerve damage from my C-section.”

In recent years, Kimberly-Clark Corp. has sought to promote incontinence products to younger women, introducing a line of Poise pads for what it calls “light bladder leakage.” Television ads have featured comedians Whoopi Goldberg and (as the Poise Fairy) Kirstie Alley. The company is also marketing a new line of Depend disposable adult diapers, worn by women and some men in their 30s and 40s, through a campaign called Underwareness that reads like a public service announcement.

“I’m all for de-stigmatizing incontinence products,” said Nack, “but not for normalizing it such that the childbearing causes are hidden and assumed to be a normal part of life.”

Doctors also are harmed by an almost universal silence about what can go wrong in childbirth. In delivery and emergency rooms, medical professionals work under high pressure and sometimes extreme uncertainty, observes Banker, who pays special attention in interviews to how obstetricians and others navigate crisis situations.

“They’re really just supposed to be able to provide that medical care and know exactly what to do every second … and keep people alive under all circumstances,” she said.

Once medical training is complete and you’re the expert, it’s hard to have frank conversations, even with colleagues, about multiple ways to handle crises. Banker thinks matters might improve “if it became more standard for doctors to be able to debrief after serious or complicated situations, if it became common for them to acknowledge things that maybe they would have wanted to do differently.”

To start more conversations, the researchers are sharing insights from the study. Already, their work has informed The National Partnership for Maternal Safety, an initiative from the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care that reaches out to every birthing hospital in the country.

To fill holes in popular guidebooks on pregnancy, the team also plans to communicate directly with women and people in supportive roles, sharing research findings with organizations like Lamaze International and on “mommy” blogs.

If outreach to women changes how some of them look at a pregnancy or at the whole question of having children, says Conner, that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

“Having kids in the future is something that I have considered, and that hasn’t changed at all,” she said. “I just know that I will be much more informed than the average woman.”

Finding out what to look for in health care professionals and hospitals and knowing “how to build a support system of family and friends” are major advantages, says Conner. Expectant mothers have some control over those things. Bottom line: being as prepared as possible is a different proposition from knowing what to expect.