Pastor Gerry and the trouble-makers

In a burst of student activism 30 years ago, Cal Lutheran sold off the last of its stock in companies doing business in apartheid-era South Africa, and members of the student congregation joined an underground struggle to protect Central American refugees. What exactly got these Samaritans off their donkeys?

None of them came to join a march or carry a sign. In fact, the most politically active Cal Lutheran students of the mid-1980s do not recall organizing demonstrations. The campus, of course, had seen protests in years past, especially during the Vietnam war. But it was hardly known as a hotbed of student revolt.

On his arrival, Jim Lapp ’86 hoped and expected that the Lutheran liberal arts college (not yet a university) would be “more of a Christian Disneyland, where everyone kind of believed the same thing and … it was all about the internal or personal spiritual quest, as opposed to the rest of the world and its problems.”

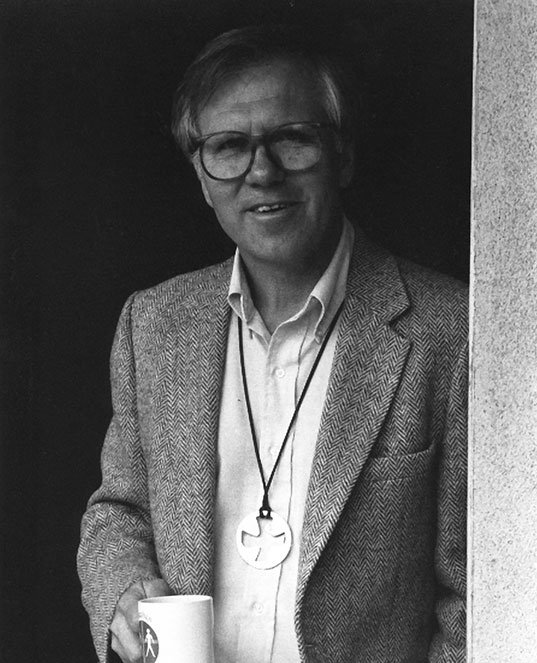

“But it was very soon,” Lapp said slowly, starting to chuckle, “that I learned” that the first campus pastor, the Rev. Gerry Swanson, H’07, “was going to challenge that perspective.”

Armed not always with certainty, but with new confidence about their ability to act in the wider world, students scored two major victories in the spring of 1986. First, in February, they got the college to sell all of its investments in companies doing business in apartheid-era South Africa, beating the University of California system to the punch by several months. This was the only time that Cal Lutheran has ever divested endowment funds on moral grounds.

The month after that, in March, members of the Lord of Life student congregation voted to support the so-called sanctuary movement that was protecting Central American refugees of war from deportation and violence back home, typically by housing them in U.S. churches. The students raised money for a safe house in Los Angeles in cooperation with peers at eight other local colleges and universities. The action was personally risky for students because the underground movement housed asylum-seekers in defiance of U.S. law.

Credit for the accomplishments, to be clear, goes to the students who worked to make them happen. Picture yourself as an undergraduate again, maybe 19 years old. There is something profoundly awkward about approaching the business manager of the college to have a word about the endowment portfolio; and who wants to worry about earning an FBI record with their degree?

But 30 years later, three student-activists feel gratitude about the movements they joined and the mentoring they received. They say they had the sort of experiences that colleges are always promising to prospective students. They found out who they were and came nearer to knowing what to do about it.

“It wasn’t tons of us. It wasn’t half or even a quarter, but some of us came with concrete commitments to justice. For me, those weren’t super well-formed, but CLU became a place where I could articulate those and put them into practice,” said Jennifer Simpson ’88, who reported on all sides of the anti-apartheid divestment campaign as news editor for The Echo, worked to support the sanctuary movement in Lord of Life, and finally was elected student body president.

Two pithy pieces of writing come to mind for Ron Dwyer-Voss (Voss ’87) whenever he thinks of the Rev. Swanson, or Pastor Gerry, who died this July (see Page 8). One of these, a quote from the Catholic priest and author Andrew Greeley, hung in a frame on Pastor Gerry’s office wall, illustrated with the figure of a dancing Jesus. It read, “Jesus and his trouble-making go merrily on.”

“It’s OK to be making trouble if you believe that this is what Jesus would be doing,” Dwyer-Voss summed up the lesson. “Just don’t lose your joy in the process.”

The other was a letter to the editor that he recalls seeing in The Echo, containing a three-point “exegesis” of Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan. When CLU Magazinewas not able to locate the letter in paper and online archives, the Rev. Lapp produced a copy of it that he’d preserved for 30 years in scotch tape.

Swanson wrote:

1. The Good Samaritan went for a ride on a donkey.

II. The Good Samaritan saw a trashed human being.

III. The Good Samaritan got off his ass and did something.

It so happened that South African Anglican Bishop Desmond Tutu brought a similar message to the United States on a speaking tour in May 1985, when he was still the most recent Nobel Peace laureate. On stops at UC campuses, he urged students to keep demanding that their university system dump billions of dollars of stock in companies operating in the apartheid state.

Tutu told a UCLA crowd, “Don’t let anyone delude you into believing that what you do today is of little moment. Don’t let them say to you, and then believe it, that it’s merely a matter that doesn’t even embarrass the South African government. I want you to know that you are giving very considerable

encouragement to the victims of one of the most vicious systems the world has ever known.”

Swanson invited Lapp and Dwyer-Voss to come with him to witness Tutu’s forceful oratory in person at UC Santa Barbara. On the car trip back to Thousand Oaks, Dwyer-Voss said, the two young men had questions. Most involved how to dismount a donkey.

Skills were needed for the students to turn conviction into action, and not only moral encouragement. They had religion professor Byron Swanson to walk them through complex ethical questions. Sociologist Pam Jolicoeur stood out for her ability to impart critical thinking skills. From business professor James Esmay, who had grown concerned about racism in South Africa in the late ’70s while teaching in Botswana and Swaziland, Dwyer-Voss learned how to read the business press and company financial filings.

What Pastor Gerry added to this, above all, was “space” for calmly reaching conclusions, according to Simpson.

“He had a way of being engaged and very interested, but also I never felt pressure or judgment or a certain direction,” she said. “I think that quality, at least in my experience in life, is really rare.”

At a weekly series of “Christian conversations” and less formal meetings, students discussed the legacy of U.S. slavery and Americans’ obligations to South Africans. They also talked strategy. What were the implications of a year-old boycott of the country’s white-owned businesses? How much would the students’ cause be aided by official support for divestment from the American Lutheran Church and the Lutheran Church in America?

Soon, Dwyer-Voss and others were sitting in front of the Caf at lunchtime to tell classmates about Soweto shantytowns and to collect signatures on a petition. In 1985, you could speak directly with nearly every undergraduate that way.

According to the Los Angeles Times, about 500 students had signed the petition by December, when Dwyer-Voss and Lapp presented their case to the Board of Regents, an encounter facilitated by CLU President Jerry Miller. Because the proposal met with resistance, the campaign leaders were surprised that evening to receive a phone call from Miller informing them that their motion for divestment had carried. Two months later the offending investments were purged, keeping up the momentum for action at colleges large and small.

Not content with that success, members of the student congregation turned to the question of sanctuary for refugees from civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala. About 300 U.S. churches and a few cities had declared themselves in the support of the movement, arguing that the U.S. government was downplaying a refugee crisis for political reasons.

“These people were showing up on the doorstep of our country just brutalized,” said Lapp. “We had of course the very famous story of Archbishop Oscar Romero being assassinated – while giving Communion? I mean, that really hit home to us. And then we had our own Lutheran bishop in El Salvador abducted and tortured. And these were things the religious community was paying close attention to.”

At the height of a campaign lasting close to two years, the students were providing about $240 a month toward rent and expenses for between one and four people, according to a November 1987 article by Simpson, who was then the ASCLU president. Lapp briefly met the first family from El Salvador, and Dwyer-Voss recalls raising funds by asking classmates for donations in the amount of pizza money once a month. The safe house was a collaborative venture, so students met with peers from Pomona, Pitzer and Scripps colleges, Claremont School of Theology, UCLA, UC Riverside, UCSB and USC.

Trouble-making by Pastor Gerry’s charges has never ceased, and they continue to draw lessons and strength from their Cal Lutheran days. Lapp, as a pastor, and Dwyer-Voss separately have organized communities on issues such as affordable housing, and Simpson has devoted her career to challenging institutions of higher education on social justice issues.

“I’m realistic. I don’t know if our efforts made any difference,” Simpson said. “But it was just an affirmation that how we live at Cal Lutheran does matter for other people. We live in a world where there are these connections, and we do have obligations to each other to work at justice and more equitable societies and more equitable communities.

“At this very small university, we picked up these questions in a very serious way. I think that’s significant.”