Smart Justice: Chavez Ravine - Elysian Park

Introduction

The story of Chavez Ravine began during the Mexican era in California, when 27-year-old Julian Chavez moved from New Mexico to Los Angeles to invest in real estate. Chavez bought nearly 100 acres just north of the pueblo. Later he served in both the Mexican and American governments up to the 1870’s. His investment in Chavez Canyon then housed a smallpox hospital for Chinese and Mexican workers and a pioneer Jewish cemetery. Later renamed Chavez Ravine, it became the site of a reservoir for flood control, a sanitarium, a brick quarry, and petroleum development. By 1886 portions became parks and three small towns, Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop, constructed to house Mexican workers threatened by flooding from the Los Angeles River. Soon a store, a church, and a school appeared on the land designated for residential development.

In 1910, 150 miles south of Los Angeles, the thirty-year regime of Mexico’s president Porfirio Diaz ended, resulting in years of violence and instability. Suffering citizens moved north to the United States, seeking work and opportunity. Soon Chavez Ravine housed 1800 families creating a largely semi-rural Mexican-American community. However, when World War II ended, Los Angeles expanded dramatically. The Los Angeles Housing Authority, funded by the National Housing Act of 1949, voted Chavez Ravine “under-utilized.” They decided to buy-out the homeowners using eminent domain to secure the land for low-income housing. Despite protests, plans to remove the population by 1960 succeeded. With homes bulldozed and the housing project shelved, the Brooklyn Dodgers received the land to build Dodger Stadium. The remaining houses sold for $1 apiece to become movie sets, including the Finch home in the movie "To Kill a Mockingbird" (1962).

Aurora Arechiga Vargas

Eight thousand feet above sea level, north of Mexico City, the Spanish commandeered the pre-Columbian mining sites of Zacatecas in 1548. Like the people before them the Spanish intended to exploit the silver mines in the region. Even in the 21st century, Zacatecas produces 17% of the world’s silver. Since the ore travelled a dangerous path to the capitol, a railroad was built in the 1880’s linking Zacatecas to Mexico City to the south and to United States border to the north.

Eight thousand feet above sea level, north of Mexico City, the Spanish commandeered the pre-Columbian mining sites of Zacatecas in 1548. Like the people before them the Spanish intended to exploit the silver mines in the region. Even in the 21st century, Zacatecas produces 17% of the world’s silver. Since the ore travelled a dangerous path to the capitol, a railroad was built in the 1880’s linking Zacatecas to Mexico City to the south and to United States border to the north.

Regrettably, the 19th century witnessed Zacatecas become a battleground. In 1810 Mexico rebelled against Spain, then the French arrived in 1864, and, finally, during the Mexican Revolution, Pancho Villa’s northern division defeated the federal army in the Battle of Zacatecas on June 23, 1914. At least 7000 people died, resulting in instability, crime, and civil unrest.

For one man, Juan Cabral y Carlos, the revolution spelled trouble. By 1914 he had five children, had buried his first wife, and his eldest daughter, Abrana, was 17 years old and at risk from the soldiers. It was decided she would marry Nicholas Ybarra and immigrate to Arizona where Nicholas could work in the copper mines of the Phelps Dodge Company. They crossed the border in October 1916, but just six months later Abrana gave birth to a daughter and became a widow. Her husband’s death certificate cited cause of death as syphilis.

Although the census described Abrana as a housewife, one must assume she was far more than that, eking out a living and caring for a newborn. By 1920 she had remarried another émigré from Zacatecas, Manuel Arechiga. Aurora Arechiga, their first child together, arrived in 1921. Still looking for a place to call home and hearing of jobs on the railroad, the family migrated to a small village in Los Angeles called Palo Verde.

Aurora and her five siblings grew up in Palo Verde and just before Christmas 1938 she married Porfidio Vargas. As the Great Depression gave way to World War II, their daughters joined the household while newspapers reported Germany’s sweep into Poland. On December 7, 1941, headlines announced Pearl Harbor had been bombed; war had begun! Porfidio enlisted in the Armed Forces and headed for Europe in June 1943. There his 9th Infantry Division participated in the Normandy invasion and then pushed on toward Germany. On December 14, 1944, Porfidio died fighting in the Battle of the Bulge. Aurora became a war widow at twenty-three years old.

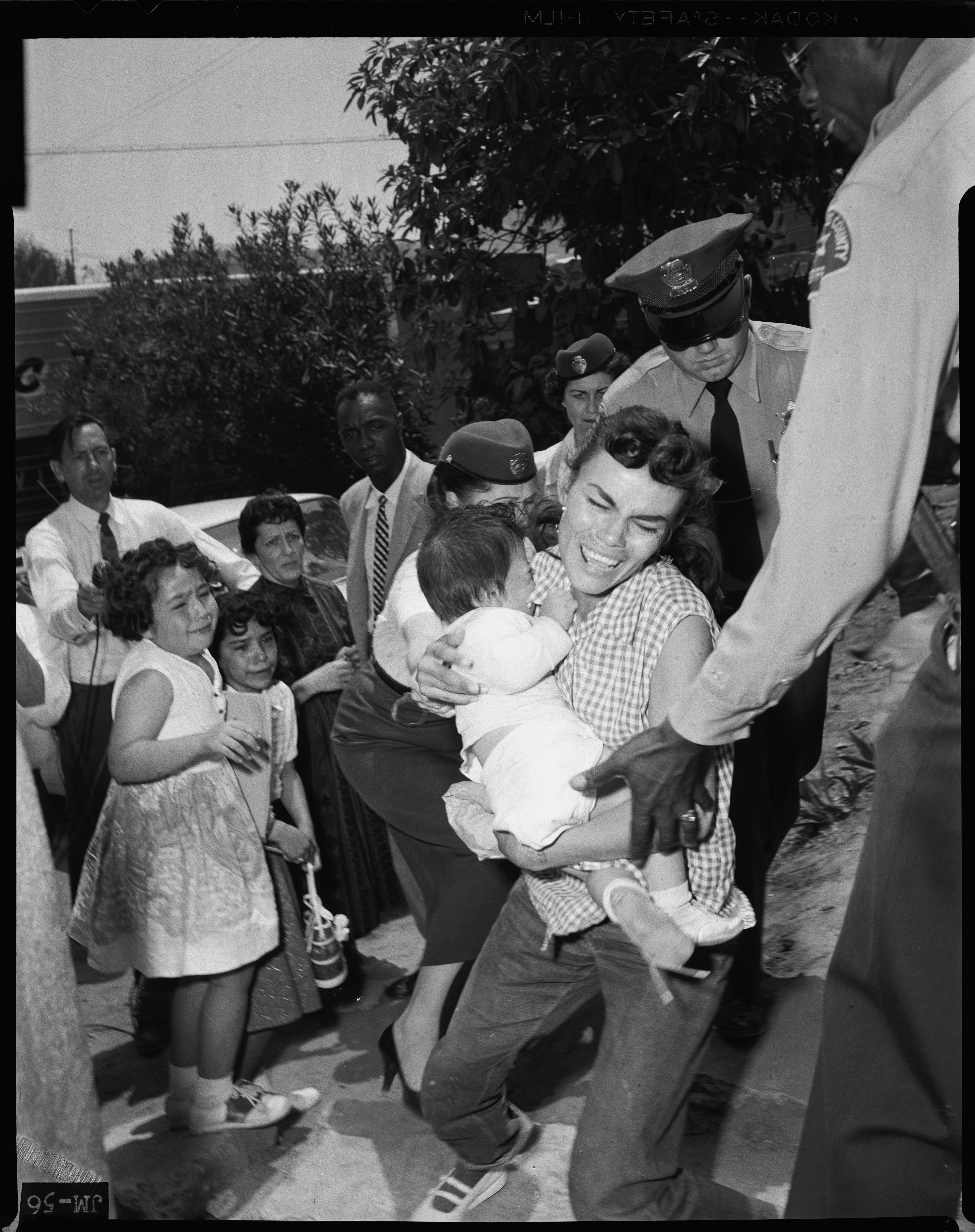

While the soldiers came home and the economy boomed, Aurora’s family stayed in Palo Verde. In 1949, word spread that a federal housing bill might bring home improvements. However, those improvements meant Palo Verde and the nearby towns of Bishop, and La Loma were to be condemned. Although eminent domain payments were offered, Aurora fought to stay in her home. On May 8, 1959, police forcibly carried her out; she was arrested while her daughters looked on and spent thirty days in jail for her angry resistance. A newspaper story on May 11, reported that Aurora had suffered a “breakdown” and hospitalization was suggested. Instead, a doctor sedated her and put her to bed in the tent where her house once stood.

Pictured: Aurora Vargas being arrested by LAPD, 1959, from Los Angeles Times Photographic Library, https://www.latinousa.org/2017/11/08/battle-chavez-ravine-pictures/.

Cruz Cabral

On June 3, 1943, two brothers faced decidedly different obstacles. That month the older brother, Sgt. Cruz Cabral, prepared to deploy with the Fourth Marine Division to the South Pacific where would be wounded four times, awarded the Purple Heart and Bronze Star medals and his unit would receive the Presidential Unit commendation as they fought in the Gilbert and Mariana Island campaigns, occupied Saipan and Tinian Islands, and assaulted Iwo Jima in early February 1945. Cruz Cabral was 23 years old that year and had been married four months. His wife was at home in Los Angeles on Malvina Avenue.

On June 3, 1943, two brothers faced decidedly different obstacles. That month the older brother, Sgt. Cruz Cabral, prepared to deploy with the Fourth Marine Division to the South Pacific where would be wounded four times, awarded the Purple Heart and Bronze Star medals and his unit would receive the Presidential Unit commendation as they fought in the Gilbert and Mariana Island campaigns, occupied Saipan and Tinian Islands, and assaulted Iwo Jima in early February 1945. Cruz Cabral was 23 years old that year and had been married four months. His wife was at home in Los Angeles on Malvina Avenue.

Also living on Malvina Avenue was the youngest brother “Gene” who greatly admired his five brothers serving overseas. He wrote them of the news at home, including the new Navy and Marine Reserve Armory built down the street on Chavez Ravine Road, now Stadium Way. He also reported on the “zoot suit” fad. Zoot suits were long roomy jackets, called “drapes”, “ankle-choker” pants, and included a long watch fob or hat. In opposition to the military haircuts of the middle class, the zoot suiters grew their hair longer, and wore it in a greased ducktail. Their girlfriends wore short “hobbled” skirts, pompadours and high knee socks, The style originated with African American jazz clubs in East Coast cities, but became a symbol of young adolescence, or, some argued, youth delinquency.

On May 30, 1943, zoot suitors and sailors exchanged angry words and punches near the Long Beach Harbor; one sailor was injured. The zoot suits were viewed as a way for non-military youth to flaunt their freedom or lack of patriotism, depending on the viewpoint, and the yards and yards of fabric defied the cloth rationing restriction that forbade cuffs, etc. The new Navy and Marine Reserve Armory then saw hot-headed young recruits head into the nearby neighborhoods to get revenge. Luckily, Gene stayed home, but those who did not were threatened, stripped of their suits, and the material was burned. In response, zoot suits were outlawed for the remainder of the war, military personnel were confined to barracks/ships, and antipathy grew. The Corona Daily Independent on June 24, 1943, quoted Gene, “I remember writing my brother…. He was my hero. I wrote him in respect to the riots. He couldn’t believe it. He was so ticked off. Here he was fighting, and we were getting beat up because of our dress.”

Ultimately, the confrontation reinforced fears and prejudices. Some argued the “riots” were part of a Communist plot while others argued the problem was ethnic and economic discrimination. These issues then impacted the funding of the Housing Act of 1949, which allowed Malvina Avenue neighborhoods condemned for Elysian Park Heights, a low-income project of two-dozen 13 story buildings and another 160 two-story homes. Frank Wilkinson, Assistant Director of the Los Angeles Housing Authority, spearheaded the effort until he was accused of being a Communist and jailed. The City Council then looked for a buyer and found Walter O’Malley, amid looking for a place to move the Brooklyn Dodgers. And so, Cruz Cabral found himself facing the bulldozing of his family home in 1959 and holding the sign “This is what we fought for” in the local newspaper.

Pictured: Cruz Cabral and his aunt Abrana Arechiga standing amid ruins of home, 1959, from Los Angeles Public Library Collection, https://laist.com/news/la-history/dodger-stadium-chavez-ravine-battle.

Frank Wilkinson

Frank Wilkinson, former Los Angeles housing official and civil rights activist, was born in Michigan on August 16th, 1914. Raised in a two-parent household that traveled across the country, the Wilkinson family eventually settled in Beverly Hills, California in 1926. The family was staunchly Methodist and members of the Republican Party, both of which compelled Frank to be involved in political and religious groups in college. For a while, Wilkinson wanted to join the ministry, but when he was travelling through Chicago on his way to the seminary, he witnessed widespread poverty, sickness, and suffering for the first time along Maxwell Street. Disturbed by what he saw, he lost his faith in religion and dedicated his life and career to eliminate poverty everywhere.

Frank Wilkinson, former Los Angeles housing official and civil rights activist, was born in Michigan on August 16th, 1914. Raised in a two-parent household that traveled across the country, the Wilkinson family eventually settled in Beverly Hills, California in 1926. The family was staunchly Methodist and members of the Republican Party, both of which compelled Frank to be involved in political and religious groups in college. For a while, Wilkinson wanted to join the ministry, but when he was travelling through Chicago on his way to the seminary, he witnessed widespread poverty, sickness, and suffering for the first time along Maxwell Street. Disturbed by what he saw, he lost his faith in religion and dedicated his life and career to eliminate poverty everywhere.

By the 1950s, Wilkinson worked for the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles. In the years after World War II, there was a massive population spike in the Californian city. Proposed structures, including homes, businesses, public venues, and roads, were divided between public and private groups. As the head of the Housing Authority, Wilkinson was tasked in 1952 with leading a project to replace the neighborhoods in Chavez Ravine, then-home to over 300 Mexican-American families. Wilkinson envisioned a series of 10,000 housing units with public parks and community centers. Proposed as “Elysian Park Heights,” Wilkinson believed that the public housing project would not only help the impoverished peoples of Chavez Ravine, but would also serve as a way to further advance racial equality. As the Red Scare of the 1950s grew more expansive, the perception that public housing was a Socialist plot terrified the general public in Los Angeles. Private parties with real estate interests in the same area also campaigned against the public housing plans, often presenting themselves as the better, “more American,” alternative to the project.

Further controversies surrounded the project as Wilkinson was summoned by the California Anti-Subversive Committee to testify whether or not he was a Communist. Refusing to answer the question, he and nine other housing officials – including his first wife, Jean – were fired from the project and were blacklisted from every group, public and private, they were involved in. At the same time of his firing, the 1952 Mayoral Election ended with the defeat of the progressive incumbent mayor Fletcher Bowron, who supported the housing project. Norris Poulson, a conservative politician endorsed by several major business groups and the Los Angeles Times, won the Election and formally cancelled the housing project in 1953. Most of the Mexican-American families who lived in the Chavez Ravine either moved out on their own, or were bribed to leave, throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, and those who opted to say and resist any new developments were forced to leave once the city government decided on what would be done with the land. In 1958, Los Angeles Councilman Kenneth Hahn convinced Walter O’Malley – then-owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers – to move the team to California, making their new home stadium in Chavez Ravine. Construction of the Dodger Stadium began the following year, and it formally opened on April 10th, 1962.

The dismissal of the housing project was not Wilkinson’s final venture in public affairs, as after a brief 1961 imprisonment by the House Un-American Activities Committee, he was determined to “fight for the [HUACs] abolition.” Co-founding the National Committee Against Repressive Legislation, Wilkinson spent the rest of his life making public speeches and protesting against the HUAC, and other laws and systems that he considered unconstitutional. The HUAC was abolished in 1975, upon which Rep. Robert F. Drinan (D-Mass.) congratulated him for his contributions to the fight. In 1995, the City of Los Angeles issued a citation praising Wilkinson for his civil liberties advocacy, after which he received a lifetime achievement award from the American Civil Liberties Union in 1999. Wilkinson eventually died on January 2nd, 2006, survived by a total of six children, nineteen grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren.

Pictured: Portrait of Frank Wilkinson, 1952, from Digital Collections of the Los Angeles Public Library, https://tessa.lapl.org/cdm/ref/collection/photos/id/23679.

Lesson Plans

To better understand the biographies we have provided, and to contextualize the field trips to the historical sites, a series of lesson plans have been provided for the use of students and faculty. They may be read online, downloaded, and printed as needed.

Understanding the Past

Click here to download "Red Scare and Dodger Blue" lesson plan.