The Cal Lutheran connection

Former Kingsmen teammates are rising stars in college football coaching

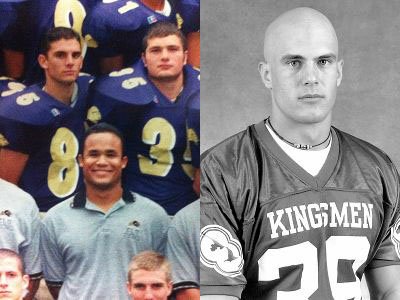

Wisconsin defensive coordinator Dave Aranda and Ohio State offensive coordinator Tom Herman started off as teammates at Cal Lutheran.

Dave Aranda was working the graveyard shift as a truck stop security guard when he first visited California Lutheran University.

The former standout linebacker at Redlands High School in Southern California was set adrift in life when a chronic shoulder injury derailed his playing career. He attempted to join the Navy, but he couldn’t pass the physical with a bad shoulder. He didn’t care much for school at the time. He coached the JV squad at Redlands and made ends meet by finding solitary work in the shadows of a town ripped from a Steinbeck novel, built up around orange groves and rail yards.

"I was lost a little bit," Aranda said. "I had the midnight shift. It was crazy. I had honestly forgotten about all that. It almost seems like another life."

Aranda’s new life, and the path to his current job as Wisconsin’s defensive coordinator, started at Cal Lutheran. He visited with an old high school teammate because he wanted to play football again. He missed it enough to pay the five-figure tuition bill to give his shoulder and the game another shot.

Their host for the weekend was a charismatic sophomore wide receiver. He was a quick-witted man-about-campus, a future MENSA member who put his broadcast-worthy voice to work as the public address announcer for basketball games on campus. During timeouts, he was known to jump up on the scorer’s table and dance to whatever music filled the small gymnasium. That was Tom Herman, now the offensive coordinator at Ohio State.

Just shy of 20 years later, both men are rising stars in the college football coaching world as they approach 40 years old. Both oversee units that rank in the top five nationally in their respective tasks. Herman's offense scores 44.1 points per game. Aranda’s defense allows 16.8 per game. Herman is a finalist for the Broyles Award, given annually to the nation’s top assistant. Aranda is not, but frankly, should be. On Saturday night, the former college teammates will go head-to-head in a battle for the Big Ten championship.

Cal Lutheran’s campus, home to roughly 2,800 undergrads, occupies less than half of a square mile of former ranch land in Thousand Oaks, 40 miles up the coastline from Los Angeles. Somehow, its Div. III football program has turned that plot of land into the country’s most unlikely breeding ground for coaches.

The "Cal Lu guys" can be found all across North America. Will Plemons, a former teammate of Aranda and Herman’s, coaches the defensive line for the CFL’s Toronto Argonauts. There is Denver Broncos secondary coach Cory Undlin and New York Giants’ quarterback coach Danny Langsdorf. Both started their careers as Kingsmen in the '90s. Dallas Cowboys defensive coordinator Rod Marinelli (’72) is the senior statesman of the group, which includes dozens of other coaches scattered throughout college and professional leagues.

"There’s been a bunch of us," Herman said. "I take a lot of pride in Cal Lutheran, and I think Dave does as well. ... I don’t know why there are so many of us. I wish I had a sexy answer for that, but I don’t."

Humble Beginnings

In the spring of 1958 -- a few months before the words "Cradle of Coaches" made their debut in newsprint in reference to Miami University in Ohio -- Cal Lutheran’s Board of Governors gathered for the first time on what would become their new campus. They decided then that the school would open its doors three years later. Two years after that, in 1963, the Dallas Cowboys asked if they could hold summer training camp at the new school, and a connection to football was born.

The roots of Cal Lutheran’s massive coaching tree start with Bob Shoup, the program’s first head coach. The NAIA Hall of Famer won a national championship for the school in 1971. In his 28 seasons, he coached 186 players that would go on to coach at some level. That is nearly one out of every four men that put on a jersey during Shoup’s career.

Cal Lutheran has a strong education major. Many of its graduates go on to be high school teachers, and the part of that population that played for Shoup usually decided to coach at their future schools.

"There were a lot of teachers and high school coaches that came out of here in the early days," said Ben McEnroe, the school’s current head coach and an assistant during Herman and Aranda’s time. "It’s just really part of the culture here."

Aranda’s high school coach was a Cal Lutheran graduate. Herman was introduced to the school by a high school baseball coach who played for Kingsmen. That culture, and the resulting web of high school coaches that stretches across California, might not have tapped into the state’s rich supply of high school super stars (It’s a Div. III program after all), but it helped set up a pipeline for a particular type of prospect.

"Our approach when I was there," said Scott Squires, the man who recruited both Herman and Aranda, "was we always want to recruit guys that loved football. If we got guys that really loved the game, we knew we could push them."

Squires’ plan created a pack of gym rats. Cal Lutheran became a haven for undersized football junkies. They crowded into a weight room that was roughly the size of two small offices stapled together. Position meetings before practice were held in converted chicken coops. ("They were all plastered up, but yeah, that’s what they used to be," Aranda said.) Then the team would jog down a half-mile gravel road to get to its practice field. And mostly, they were thrilled for the opportunity. When Aranda toured the no-frills facilities and saw the players’ intensity, he knew he had found his tribe.

It was normal for the guys to hang out and break down defensive schemes in their dorm rooms at night and draw up plays during class, planting the seeds of future coaching careers.

Herman, who transferred to Cal Lutheran from UC Davis in search of playing time, loved the game enough to keep coming back after 13 knee surgeries. At one point, doctors had to grow a piece of his cartilage in a lab to create enough of it to properly patch the joint. He rarely practiced during the week as a senior, then made a handful of circus catches each Saturday on his way to an all-conference season.

Aranda’s shoulder issues tested his will to play, too. He missed the start of his freshman season while recovering from surgery. In one of his first practices back in pads, he and a lead-blocking fullback collided with so much intensity that he split his helmet in two -- mashed the face mask and cracked it right down the seam.

"That’s my one claim to fame of playing football," he said about the mangled headgear. "I loved the game so much, but I never played. I was always injured. I think I lasted about one more day after that and I was done."

Budding Careers

Injuries let Aranda get an early start on his coaching career. He hung around at Cal Lutheran and started working as a student assistant coach. Most of his free time was devoted to scraping together enough gas money to drive to USC, UCLA or Arizona State so he could pick the minds of their defensive coaches. By the time he was wrapping up his philosophy degree as a senior, he was promoted to Cal Lutheran’s linebacker coach.

The background in philosophy turned Aranda into a unique coach. He doesn't lead with the same defiant confidence as most coaches, instead contemplating new ways to solve offenses up until the last possible minute during a week of prep work.

"Much like in a philosophy discussion, there’s an argument," he explains. "What is the central major point there? What is holding up that major point? You have to break it down piece by piece. You’ve gotta be all encompassing, man."

When he wanted his secondary at Cal Lutheran to flip from a back pedal to running faster, he showed them video of top baseball base stealers ripping their arm through and flipping their hips. When he wanted to teach his linebackers to gather themselves before making a hit, they watched tape of steer wrestlers leaping onto cattle.

Herman took his motivational cues from Squires, their Cal Lutheran coach. He still uses a handful of the sayings that helped him keep going during his playing days. His experience with injuries has helped him encourage and empathize with struggling players. His contagious personality let him take control over every room he walked into as he skipped around the country from one coaching job to the next.

"Both of them are just really smart guys," Squires said. "Tom could be running a major corporation if he wanted to, but they wanted to coach."

Both men left Thousand Oaks for Texas to begin their coaching careers. They met as opponents for the first time as graduate assistants for Texas and Texas Tech. Herman and his Longhorns won that matchup. The following year Herman moved east to Sam Houston State, but visited Aranda in Lubbock so the two could help each other prepare for the season.

"I drove 10 hours from Huntsville, and I slept on his couch for about three days there," Herman said. "Over the years we’ve stayed in touch and always traded ideas."

The Cal Lu connection has continued to help its graduates after they leave campus. Aranda and his former teammate Plemons, now in the CFL, traded ideas regularly when they both coached defenses in the WAC. When Aranda’s Hawaii defense found a way to bottle up Nevada star Colin Kaepernick, Plemons (who was at Fresno State at the time) said they talked for hours to dissect how he did it. Aranda and Herman continued to spend long summer days together explaining the current trends on their side of the ball to help each other get ahead of the curve during their equally fast ascents through the coaching ranks.

The Cal Lutheran dinner reunions at coaching conventions are always well-attended events, and usually serve as a reminder of how little has changed about the solitary truck stop security guard and the public address announcer who liked to dance on table tops.

"We’d go to the coaches' conventions and Dave would be the guy that would grab one coach and take him to a coffee shop or up to the room and they’d grind out football for two days. You’d never see him," Squires, their old coach, said. "Tom would be the guy down in the lobby shaking everybody’s hands like he was a politician going for a job. By the end he would know the name of everyone in the building."

Aranda and Herman are polar opposites in personality, but proof that the West Coast’s budding breeding ground for coaches can shape all types into future successes. The common threads of a love for football and Cal Lutheran education have landed them in the same spot.

In Indianapolis, two of the country’s hottest young coordinators will match wits for a Big Ten championship. Their fellow alums, true to football-junkie form, are giddy about the chess match that will unfold. No matter what happens, a tiny campus in Southern California and its continent-wide coaching tree will have a reason to celebrate.

--- Published on ESPN.com on Dec. 5, 2014