Caring for essential workers

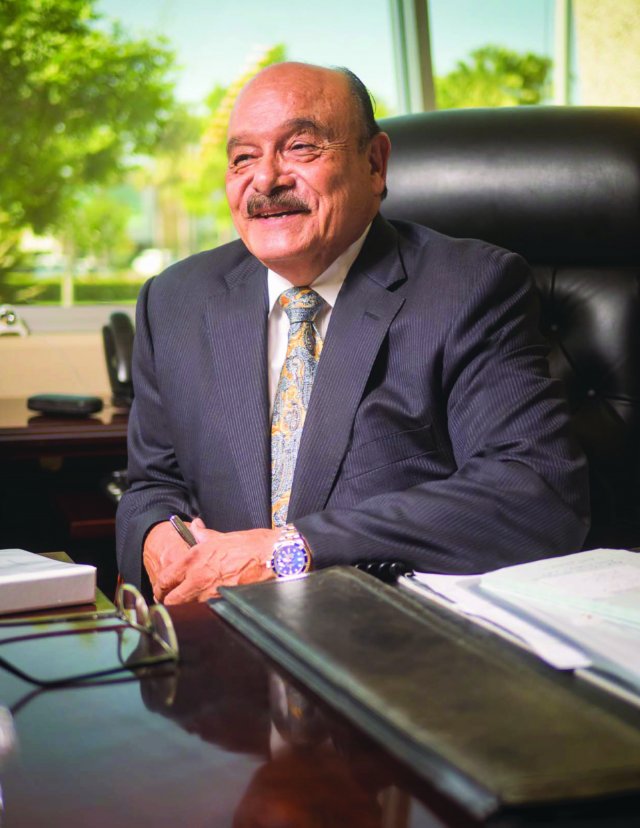

Alumnus Roberto Juarez believes farmworkers' well-being is vital, especially during the pandemic.

Roberto Juarez ’89 believes that because U.S. farmworkers feed the world their well-being should mean the world to us, but after more than four decades of delivering health care to agricultural laborers, he knows that seldom is the case — and this time of pandemic is no exception.

As CEO of Clinicas del Camino Real in Ventura County, Juarez predicted in early February that farmworkers would be among the nation’s most imperiled workforce as coronavirus dug in.

“How they live, work and get to work puts them most at risk,” said Juarez, who grew Clinicas from operations out of two motel rooms in 1978 to 15 community health centers serving more than 100,000 people, placing it among the country’s largest medical providers for farmworkers and their families.

His worst expectations came to pass after California Gov. Gavin Newsom declared farmworkers to be essential workers. In July health officials reported fieldworkers, who make up 2% of the county’s population, accounted for 7% of its positive coronavirus tests.

Ventura County’s two biggest COVID-19 outbreaks struck at an agricultural guest-worker housing complex and an avocado packinghouse.

The first farmworker to test positive in Ventura County is a Clinicas patient, Juarez said. The private HMO’s medical director then put in place safeguards to keep infected patients out of the waiting and examination rooms while getting them critical medical support. Greeters were posted to ask arriving patients those now-familiar questions about COVID-19 symptoms.

Clinicas immediately anticipated that population’s unique vulnerabilities in a pandemic, said Juarez, who grew up working-poor himself and went on to help write the state law establishing the farmworker health program and to chair a Clinton administration panel on migrant health.

Due to the high cost of housing on the state’s Central Coast, often several farmworker families share one dwelling. They often vanpool to work, sometimes with as many as a dozen riders.

Those from Indigenous cultures may practice a system of trading off caring for children and the elderly from multiple households, which also could accelerate community spread.

Because Indigenous languages such as Mixteco, Zapoteco and Triqui have no written component, Clinicas teamed up to provide public-service announcements about COVID-19 to the county’s 20,000 indigenous immigrants through Radio Indigena, which broadcasts in their native tongues.

As the pandemic wore on, Clinicas staffers determined a dearth of studies left them in the dark on how best to communicate to their patients the evolving recommendations to prevent coronavirus infection.

They compiled a questionnaire and surveyed 400 patients. Juarez shared the survey with what he calls his “brother clinics” up and down the Pacific seaboard so they could poll their patients.

Of all the classes Juarez took at Cal Lutheran, he cites statistics as one on which he frequently draws.

“At CLU I learned how important it is to make decisions based on objectivity,” he said.

A tough-talking Vietnam vet known to confront bureaucrats, Juarez tempers his edge with respect for laborers stemming from his boyhood in Oxnard’s La Colonia. Recently, he paid mariachis to perform at a drive-through “feed the front lines” food pantry to lift the spirits of recipients and put some coin in the pockets of the musicians who lost most of their work when COVID-19 regulations prohibited large gatherings.

“I consider these people to be the salt of the earth,” Juarez said. — Colleen Cason